Anspach & Hobday

A Modern Classic

Written by Jesús Olano—Photos by Jesús Olano; London (UK), 23/01/2020 beerbayOU

It's a sunny morning in Eastern London, as we go down Druid Street heading Bermondsey railway arches. Bermondsey was once a thriving comercial area, until it slowly died out. But eight years ago, a new wave of London craft brewers started to establish here. Their business started to flourish in what now is called “The Bermondsey Beer Mile”.

One of the first brewers to establish were Paul Anspach and Jack Hobday, founders of Anspach & Hobday. Paul welcomed us at his taproom and original brewery under the arches.

How did you meet each other and what took you to start a brewery?

Paul: Jack and I, actually met at kindergarten when we were about three—so we've known each other a long time. We went to school together and then we ended up both going to university in London where we shared a flat for a few years. Towards the end of my time at university, I was working in a wine shop. And that's how I got into good quality alcohol and specifically beer. By then, one of Jack’s professors had given him a basic homebrew kit—the sort of sugary goop in a can you add water to. I gave it a go, but I didn’t think too much on it. Then as we kind of got more and more into drinking beer, we decided to start making it, but only out of interest. Just drink for enjoyment.

We started giving out the beer we were making in the wine shop, where I was working, and people were enjoying it. We had people asking us if this was a business that we were pursuing. We took it as well to a couple of wine shows, where there were TV personalities—wine folks. We were giving it to them and basically to anyone that we could get feedback from. And it was all coming about really good—that was with The Porter, the third recipe that we did.

“Within a year of homebrewing, the idea to actually become a business was kind of born.”

So, we just kept doing that, and I'd say within a year of homebrewing, the idea to actually become a business was kind of born. Then, we met a small group of people who were interested in investing in something like a brewery. They wanted to help us come together, both with small financial investment, and also with their experience in the food & drink sector.

Yeah, that's pretty much it! So, it was quite a short time from homebrewing to get in this space. Only about two and half years.

How did you decided to do a crowdfunding, something that was not so popular back in those days?

Paul: Actually, it wasn't, especially for breweries. It was Kickstarter, which isn’t just a crowdfunding. You don't get shares in the company and it's just for perks—T-shirt, etc. It must have been Jack's idea to go for it—I can't remember specifically knowing that much about Kickstarter at the time. It was only for a small amount of money. We thought the idea was what it would do and obviously we'd get some money, which is great. I think we were looking for 2,500 £—we ended up getting 5,000 £, which enabled us to get our very first brew kit that we had here, a very small one.

“We had about 400 people investing. These are people that we are still in touch with today and they still come here to the taproom.”

But it ended up being a good way to tell a lot of people—beyond, friends and family— about what we were doing. We had about 400 people investing. These are people that we are still in touch with today and they still come here to the taproom—five or six years down the line. Whilst it was not a huge amount of money, it got us what we needed. Having already started with a steady customer base of people who were kind of on your sides was really good. Actually, it was a good exercise to do. And it definitely helped us become a thing that people knew about and want to support.

Back then you elaborated your first successful recipe—The Porter, that you have never changed since then. Could you tell us a bit about that?

Paul: It’s funny, the first two beers that we made when we started doing proper homebrewing—all grain IPA’s—they were terrible. So we decided to change tacks and try porter, as it is a very simple recipe—four grains and then two hops. Then an American yeast, which is slightly unusual for an English style porter—but we just wanted something very clean. Keep it pretty simple.

And it all came together nicely. Actually, I can remember the first taste of it we had. It was really good. Often, we used to go into beer shops and bars or whatever. And the staff, is always getting some homebrewing from people which is normally terrible—we have to be nice about it. But with The Porter, they were like, “this is actually good”.

“The first two beers that we made when we started doing proper homebrewing—all grain IPA’s—they were terrible. So we decided to change tacks and try porter.”

One of our very first customers was a shop in Richmond, in the West of London—we took them our first batch of The Porter. And they told us “as soon as you do this, we’ll probably buy it”—and they did, which is nice. It's a very classic style. It makes sense that it worked for us back then, because a lot of what determines whether beer is going to be any good or not is the water. And by that time we didn't understand water chemistry. Our London water doesn't fit IPA’s and Pale Ales but it works nicely with dark beers—the roasted malts give you some acidity which helps to bring down the hardness in the water. So, for very naive brewers, porter is always going to be a good place to start.

And it also makes sense because historically porter is the beer of London. It’s the same story all over the world. Whatever the main base style is, it's whatever works well with the water.

We've scaled it up now. We started brewing it at 20 liters and now we're up to 4,000 l batches. We've had to change the amount of everything, but the basic ratios stays the same.

You actually can say that it tastes the same that in the first batch.

Paul: Yeah, absolutely. Every time we've scaled it up, it's kept its character, which is really nice. It's nice to have something in the front of our range that has been with us for the whole time. It's the heart of the brewery.

You’re located at Bermondsey Beer Mile, an area that is historically linked with beer. Can you tell us a bit why did you established here?

Paul: Historically, there was lots going on around, brewing and also another food projects related with trading. But I it all completely died out. And then you're left with these funny railway arches up. Most of us occupy the first row.

“The first brewery here was The Kernel whose original brewery was just a few hundred meters down the road from us. They were actually sharing the space with a cheesemonger.”

The first brewery here was The Kernel whose original brewery was just a few hundred meters down the road. They were actually sharing the space with a cheesemonger and they backed onto a market—Mulberry Street market. So Evan [O'Riordain, founder of The Kernel] would sell his bottles pretty much exclusively on Saturday from a table in front of the brewery. And that grew in popularity. And that kind of introduced the idea of there being a thing in Bermondsey that you might come here specifically for.

When he moved to the new site, his old kit was given to Partizan. He took a railway arch close to South Bermondsey. I did the same thing. So, The Kernel was still opening there, and also in the new site, which is not far away, just half a Km away from that. Partizan was brewing on that old kit. And they were opening on Saturdays.

Brew By Numbers came next they were on the other side of the street. After then that's a span of two or three years. And then we opened in February - March 2014. Actually we were already coming to this area as drinkers ourselves visiting these places. We weren't specifically looking in this area. We were looking for a railway arch because they were good available cheap spaces, quite adaptable.

When it came up, we were actually looking in Brixton—but this one came up and ultimately happened pretty quickly. We knew what the area was like. We knew that the Saturday trail was going to be very important to us. We had two 100 l brewkits at that time, so to run it as a wholesale business wouldn't have worked at all. About 90 percent of the beer, we were selling on the weekends and we just had two bottles when whe opened—The Smoked Brown and The Porter.

The whole area has grown and grown since then. We now open pretty much the same week as folks here. Now there are ten breweries, distilleries, there's the cider place [Hawkes] with the other breweries from outside of London moving in just to put a tap for them in. It's crazy—and it keeps growing every year. Our space here that we have for the tap for now is the smallest it's ever been. But in terms of the customer doing is still growing in a really meaningful way.

“It's amazing that you can walk such a short distance, and there are so many breweries. And it’s a nice way to drink beer—it's not travelled very far, so it's going to be in its best condition.”

It gets pretty lively on Saturdays. What a lot of breweries are doing now is to open earlier in the week—maybe from Wednesday. We do Fridays and Sunday as well, which is always a little bit calmer. It's amazing that you can walk such a short distance, and there are so many breweries. And it’s a nice way to drink beer—it's not travelled very far, so it's going to be in its best condition. Chances are there's someone in the brewery that's a brewer that you can talk to if you want. And there's a lot more going on, distilleries, good food stuff... You can spend a nice Saturday here if you don't mind the crowds.

So in a few years you've transformed this area for good.

Paul: As breweries, we were young businesses, so it took a bit of time to adapt, how to handle it. Everyone had their own view on how it should be managed and what we should do about it. Everyone's kind of matured into it. Things like understanding the impacts that it has on the area and the responsibilities that we have around that.

So it's a good place now.

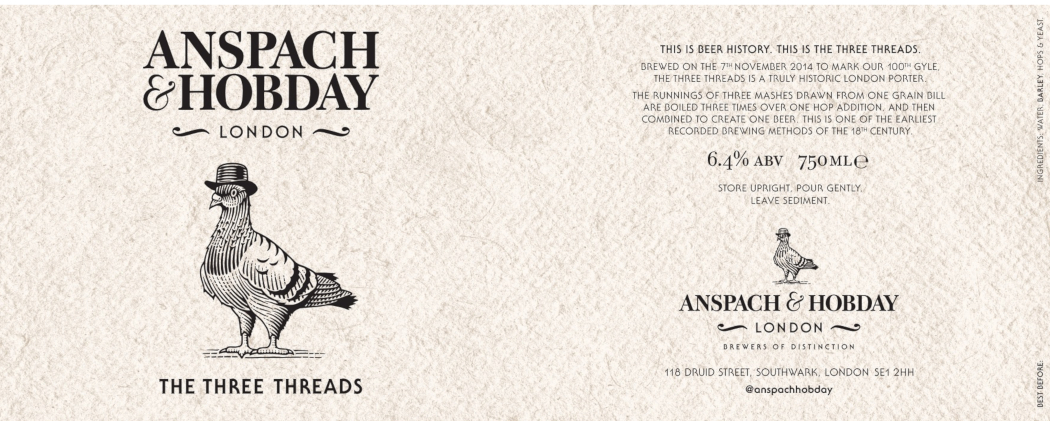

One of your main themes as a brewery is the revival of historical recipes, like the Three Threads. Could you tell us a bit the process behind that?

“You can come up with a new mushroom doughnut stout or whatever you want to do, but there's no real depth of traditional history to that.”

Paul: We do a lot of experimental temporary brews. We've always had a foot in tradition and a lot of that comes out of respect for the history and the process—beer has been important to so many cultures forever. And especially the tie in with the pop culture in the U.K. as well in history. You can come up with a new mushroom doughnut stout or whatever you want to do, but there's no real depth of traditional history to that.

We sort of accidentally started brewing with The Porter, and we then learnt a lot about the history of this style of beer. The Three Threads marks a point in brewing history, before the development of modern beer techniques—like malting, producing the malt and beer making. When malting was developed to the point where brewers could get accurate control over the temperature, they could start to define the different grades of colour that you get in the malt. Before that, it was a bit, not a mess, but brewers didn't have any control. Your malt colours would be a bit all over the place and you wouldn't have had that fine, really black stuff.

“The Three Threads marks a point in brewing history, before the development of modern beer techniques.”

The malt base we use in The Three Threads is very simple—there's just three malts. One of them is smoked because of this idea that in the malting process you would have picked up some smoke character whether you wanted it or not—as it was being done over open fires. It's the same with The Smoked Brown—and that's why we developed it.

The other interesting thing about it is the production method. There's a method of brewing called party-gyle. What you do is you take your grain, and you do your mash. Then you soak it on water—to extract sugars. The first wort of sugar you get is very, very strong. Then you’d do that process again and again and get a series of sugary waters at different strengths, and you'd use them to make different beers. Essentially you get three or four beers of different strength out of one mash—I think Fuller’s is the only brewery still producing that way.

“Rather than getting three beers—strong, medium and weak—you get one layer of light average strength.”

With The Three Threads, it's the same mashing process, but rather than treating them as individual beers, you combine them into one time fermentation. So rather than getting three beers—strong, medium and weak—you get one layer of light average strength. After the initial mash, you have the arm that spins around, that does a constant rinse of the grain. Rather than having to empty it and re-mash it, you get more of a constant flow. What it does is that you definitely get some different characteristics. You also get real complexity because you are doing an extended boil. You bring in some different characters, really complex. The ageing is very nice—it starts to develop real cherry characters. It’s been a fun beer to make. It's also difficult to make, so we don't do it often.

We recently took a similar approach with barley wines, that were traditionally made with one type of malt and there was just a very long boil—maybe up to like 24 h. All the colour comes just from the boiling process. We did a smoked barley wine with one German smoked malt for the whole grain bill and boiled it for nine hours overnight. The colour and the change of the mouth is incredible. And all that's come from the process—rather than boiling it for one hour and trying to add different grains.

You don’t take the historical recipe, you just take the process.

Paul: Yeah, exactly. Certainly that with the smoked ones. it's a nice way of brewing, it keeps us connected.

Could you tell us a bit about your Experimental Series?

“We’ve always always been pretty experimental—as we've done so many different beers over the last five years.”

Paul: We’ve always always been pretty experimental—as we've done so many different beers over the last five years. We did a lot of kettle souring, with various fruits and spices. We also do a lot of Belgian inspired beers as well and mixed fermentation stuff—a lot of the beers that we drink when we're in bars or going out around are mixed fermentation beers, saisons...

One of our brewers—Dylan—four years ago he got a load of yeast and stuff from various bottles and grew up a mixed culture of different yeast and bacteria. We've been using that since then, keeping it alive in various beers. And we've got a few barrels out the back—until we have some more space and we can do that in a meaningful way, we're just keeping it on a very small scale.

With the brett stuff, what we've tried to develop is actually being inspired by Orval—they do a clean fermentation and then a secondary fermentation in the bottle with the beer. We've done that quite a lot now with saisons, strong ales, IPAs.

What it means is we can keep all tanks clean because we do normal clean fermentation in the tanks. And then we just take off however much we're going to put into it, into a separate, bustling tank where we introduce the brett package—and we set for maybe three to six months for the Brettanomyces to develop. It's been a nice way of getting more volume out of these kind of mixed fermentation beers and a safe way to do it without destroying the rest of the tanks.

We've done six or seven now. The Experimental Brett IPA was very nice, so we'll be doing that one again soon. We did a English Bitter as a collaboration with Wiper & True. A quite traditional one, with some good amount of rye.

A lot of traditional English Styles with bretts on top.

Paul: Originally, Brettanomyces were isolated in old English stock ales. So the name means British Fungus. So that's kind of what we were we were trying to do there—old school Bitter with some bretts in there. We're doing it with different hops or grains. Whatever is a new ingredient, we want to try and find a way of doing it. It keeps it interesting.

Your artwork has a very classical English feeling. Could you tell us a little bit about it?

Paul: That goes right back to the beginning. We had some silly names before the brewery when we were just playing on homebrewing. And our surnames, they sound very good together. It has a real sense of identity, of provenance—it sounds old, it sounds established. So we kind of worked out how we wanted to present ourselves.

During the first crowdfunding campaign, we were approached by a design agency who had the primary design agency for rental. I remember getting their email and ignoring it because I thought it was scam. So they e-mailed us a couple times, and we went to meet them. We were able to give them a logo of the work and the preparation we've done, and they came up with various different routes.

“It's been a good thing for us. The idea that you have something that might tell a story.”

What we have now is one of those routes. Nice typography and the two characters representing the old and the new. It’s always two characters on the same style or profession. We got like firemen and cricket players or whatever, but one of them is of the Victorian era and one of them is modern and that represents what we do.

The illustrator is called Alan Batley, he is a bit of a legend. And he got the idea that got onboard with it. And then he came up with a pigeon as a nice icon of London. So, yeah, we're really happy with how it works, and we're going to be moving over to cans soon. So we're currently working on how we translate that.

It's been a good thing for us. The idea that you have something that might tell a story. And we haven't had to change it in five years. It gets across what we're trying to do very well. The idea of quality, respect, tradition, a bit historic, but contemporary, interesting fits nicely.

You recently finished your second crowdfunding campaign. What are your plans for the future, upcoming collabs, etc?

Paul: As you can see here, we're in a pretty small space and we need to move. We need to grow. So we did a crowdcube campaign, which it's a proper equity crowdfunding campaign—everyone who invests, even if it's 10 £, owns a share in the company. It's the same class of shares that anyone has—myself and Jack included in that. We now have something like 500 shareholders.

“We now have a new warehouse space in Canning Town [...] We're going to get some extra fermentors so we’re tripling our production capacity.”

So, we did it, which is great. The plan is we now have a new warehouse space in Canning Town, which is just a few miles from here, on the other side of the river. We're going to move all of the production over to that same brewhouse. We're going to get some extra fermentors so we’re tripling our production capacity. Get a canning line. And, various improvements to things that need to be done. And this space here, we're going to refurbish it and make it more of a more of a permanent taproom space.

We're going to keep a couple of tanks and the barrels that we have at the back and maybe add more. This will be like a mixed fermentation experimental space where we can do a lot more of that kind of brett stuff. But it will be a hopefully nice bar, a good, comfortable place to come and drink. We'll open up more during the week.

“Big, big growth plans? Not crazy. We're not trying to take over the world.”

Big, big growth plans? Not crazy. We're not trying to take over the world. We just want to get the beer further than London. You know, export is pretty good for us. We wanted to take that farther. We’re already selling more beer abroad than we do to the rest of the country.

Future collabs? We've got a couple of things that'll be released soon. We did a saison with Peninsula, and we just released a stout we made with Against the Grain. Last year we did two beers with them—a smoked lager and a Speyside whiskey barreled stout. And we actually went out to Louisville a few weeks ago to do another collab with them, a Rye Porter barrel-aged in bourbon barrels.

So that's part of the most exciting one we've got at the moment. Talking to a few other breweries, but we don't know when the new brewery is going to be up and running. So at the moment, we're focusing on making sure we don't run out of our core base.

We’ve got to have a good stock about keep our permanent customers happy and keep things kicking off.