Nøgne Ø

Reinventing A Naked Island

Escrito por Jesús Olano—Fotos por Guillermo Robles, Jesús Olano; Grimstad (Norway), 04/04/2017 beerbayOU

The small town of Grimstad looks like a peaceful place where to spend the cold norwegian winter. Surrounded by mountains, nothing tells to the casual visitor that a few kilometres away from here you can find the headquarters of one of the most revolutionary norwegian breweries, repeteadly considered one of the top 100 breweries in the world since 2006, worldwide famous for their top IPA's and DIPA's.

Nøgne Ø was founded by two Norwegian home brewers, Gunnar Wiig and Kjetil Jikiun back in 2002. Working as a commercial pilot, Kjetil got in touch with the emerging American craft beer scene back in 1990, and soon got interested and starting to develop a professional brewery in Norway. Even though they were not initially succesful at their home market, Kjetil managed to bring samples of his new beers every time he flew into the US, and soon he had created a buzz about its new brand and finally managed to get a distributor there. That were the first steps of what has become the largest norwegian microbrewery. But sometimes growing can be difficult and back in 2015 Kjetil left Nøgne Ø after selling part of his shares to Hansa Brewing, and expressing his disconformity with the new direction of the company in a manifesto. He is now living in Greece where he started a new project called Solo Beer.

After parting ways, Nøgne Ø management has spent last year redefining itself. They have a dedicated team of 26 people working hard to keep Nøgne Ø as the reference in Norwegian microbrewery scene, and recently moved into their new facilities, next to the old brewery. We were welcomed there by his Marketing Manager Tom Young, who joined Nøgne Ø in 2013, after working as a beer blogger and being one of the founders of olportalen.no.

Your name—Nøgne Ø—comes back from Henrik Ibsen

“Kjetil, started the brewery in 2002, and before that he was a homebrewer. As a homebrewer, he called himself “the uncompromising brewer”, and when he started the bewery, he was determined that the name should be “the uncompromising brewery.”

Tom: Our first brewmaster, Kjetil, started the brewery in 2002, and before that he was a homebrewer. As a homebrewer, he called himself “the uncompromising brewer”, and when he started the bewery, he was determined that the name should be “the uncompromising brewery”. He had a childhood friend who was going to make the design for him—a graphic designer—and first thing he said was that “this name was not good for a brewery. It’s long, it’s complicated, and people will not understand it. I want to make a new name for you.” And Kjetil said “no, I would like to be the uncompromising brewer”. But eventually he decided that “I can make the beers, and he can make the design”. So he came up with a local connection that was Nøgne Ø, which is mentioned in the first verse of Henrik Ibsen’s Terje Vigen poem [“på den yderste nøgne ø...”] and it means naked island, but it is not the exact translation of naked island. Nowadays, we would say nakne øy, so Nøgne Ø is old Norwegian/Danish. So it has an old historical theme, and it also has two Ø’s, that are actually special letters and it stands out, especially when you see the big Ø in the label.

So it is really related with the artwork

Tom: Yes, it was also intended to stand out from all the normal beer bottles with the strolls and the hop flowers. We wanted to show our customers that this is a whole new way in beers, because Norwegians were used to Pilsners and maybe Guiness now and them. There was no beer culture in Norway in 2002. And we found it out the hard way, because we had brewed the beers, and we were ready to sell them, but nobody bought them. They said “this isn’t beer, we cannot drink this, we cannot serve this to our customers”. Then, as Kjetil was employed by SAS as a captain, and he was flying all over the world, he took his beers with him abroad, and he got to sell them to importers in other countries—like US, England, Denmark, Sweden—that suddenly became our biggest markets. So we had beers that were originally meant for Norwegian market but there were actually just exported. 80% of the beers we made were exported. That’s also how we found out that the “Nøgne Ø” name and the “Ø” logo was quite good.

You have 4 values: quality, diversity, integrity and drinkability. As it is not usual for a brewery to state its values, how did you end up choosing them?

“So we would like to connect our employees to our values. And with the new building and things going on—like Kjetil quitting last year—, we need to take ourselves some time and figure out which direction we are taking.”

Tom: Those are the values that we are stating in our website—and we are actually changing them. We do have some ideas, we are not sure yet exactly what to do about them. But they are not used in today’s brewing and working. So we would like to connect our employees to our values. And with the new building and things going on—like Kjetil quitting last year—, we need to take ourselves some time and figure out which direction we are taking. Many things will obviously continue, like brewing uncompromising type of beers, and we are going to be innovative, and still be the leaders in the norwegian beer industry. It will develop from there.

As you said, your slogan is the uncompromising brewery, but at the same time you are the biggest craft brewery in Norway. How can you combine these two factors, that sometimes can be a little bit opposite?

Tom: Yes, it is actually that, because we are now 25 employees, that need to have their salary every month. If our brewers make beer that we can sell, then we have the responsability to sell it. But we believe in what we do, and our brewers believe that, when they make a new beer—even if it’s a very strange beer—we can sell it, and we stand for it, and say “this is a good beer, and you should drink this beer even if people in Norway haven’t tasted beers like this”. For example, we did the Norsk Høst, a beer just with norwegian ingredients that’s something that a big handcraft brewery like us haven’t made before. It cost quite a lot of money to do it. And we don’t see this as a beer that makes us a lot of money, but it’s the fun part of it, to be in front of the industry, it’s very important.

Can you tell us a little more about this beer, Norsk Høst, and how did you used the traditional Norwegian kweik in it?

Tom: We have brewed beers in Norway for thousands of years, and beer is in the Norwegian cultures. In the old times, people used the ingredients that were available in Norway, we didn’t import the malt. We used different herbs and spices from nature, and of course Norwegian grains. So we wanted to go back and make our own version of an old Norwegian beer. Since kweik was rediscovered as a yeast used in beer, and it was commercially available, we wanted to make it all Norwegian. Every farm in Norway brew their own beer in the old times. So, that beer probably tasted far from this. So we wanted to make a modern version, with things that we like in the beer. So this is not a traditional norwegian ale, it is more our perception of it. We went out in the woods—the whole company—and picked myrica gale which is a bitter herb—called pors in Norwegian—that is one of the substitutes of hops—we could have used Norwegian hops, but there are not very much available here. We also used fresh light green sprouts from the trees, and we came back home with big sacks of those. We had the kweik, and the Norwegian water was there already. So we bought hand-made malt from a guy from Oslo. And we went on to brew the beer, that has already got some recognition from a Norwegian organization that rewards fine Norwegian food and drinks, and also was rewarded beer of the year in Norway.

You recently (in 2016) moved to your new facilities here in Grimstad. How do you think it has affected your beers and your processes?

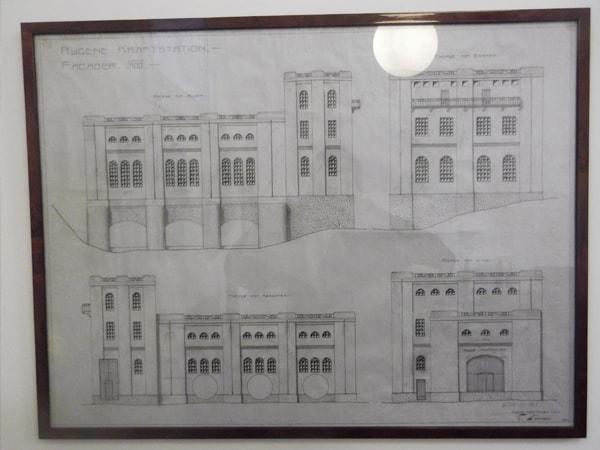

Tom: We actually moved in a couple of months ago. We started building the brewery in September last year, and it was more or less ready in October 2016. What we did is that we moved all the equipment that we have in this building in there. So the only new investment we made was buying 10.000 liter tanks for fermenting. And the rest is our own brewery. We made some little adjustments to make it more automatic, but appart from that, it’s the same equipment that we had. So it still makes the same beer, and we are very happy for that, because we were a bit afraid that doubling the capacity for tanks and kettles would affect the taste. But our taste panel has said that the beer that we brew there is fine. So we’re happy with that.

And it is a totally new routine. In the old building, there’s a lot of malt in the walls, which is not very higienic, it’s difficult to clean. So in here we have a whole new regime on cleaning. We don’t have people walking it and out. They have divided it into clean zones. So when we have guests here, they will be able to go to the second floor, and look down in the brewery, but they won’t be able to move around and touch things at the brewery. I think we have made quality control much better, and that’s a very good thing, because infected beers are always a hassle.

Kjetil Jikiun, who was your head brewer, quitted in 2015. How has that affected the brewery, and which new directions are you chasing now?

“It’s been a battle for all of us. Kjetil started the brewery, he was Nøgne Ø in person, and he is the most influential and most known brewer in Norway. His face and his appearance here at the brewery was very important for Nøgne Ø.”

Tom: It’s been a battle for all of us. Kjetil started the brewery, he was Nøgne Ø in person, and he is the most influential and most known brewer in Norway. His face and his appearance here at the brewery was very important for Nøgne Ø. Many of us were very afraid about what will happen, because Kjetil first sold his shares to Hansa, he initiated that sale, and eventually he was going out. But he went out a little sooner than expected. You probably read his Manifesto , so you know that things haven’t been very friendly between Kjetil and some of the other owners, and also a lot of the employees. We all look up to Kjetil, we are very thankful for what he did with Nøgne Ø. And part of this, the values and everything, is something that we have to do by ourselves now. We have very skilled brewers, we have creative managers that are very talented and very good at finding new directions, and new beers, and new tastes. And I think that we are very capable to stand on our own feet now, because we have everything in place, we have the people that we need, and we have the ideas.

So, we miss Kjetil, we miss his person, because he is a very charismatic person. When he comes into a room, people notice it. Not only the fact that he is two meters high, but he is a very nice guy. We wish him luck in his new endeavours in beer and wine, as I heard he is making in Greece. And he is welcome here anytime. He’s been with us at the Christmas parties last years, his wife is still working here as export manager. So the connections are there, but we cannot work together. Unfortunately. It is a sad story, but you know, business starters tend to have a very strong mind, many ideas and specific ways of doing things, and Kjetil was all over the place with his ideas, and he wanted to control marketing, sales, the brewing, and everything. When we suddenly were 20 people here, it was difficult for him to control everything. So when people had ideas that he wouldn’t have suggested, then it didn’t go well. It was a process of tiring each other out.

Looking into your collaborations, as stated in your web, so far you have made 56 collaborations. How has Nøgne Ø culture been influenced by working with so many different breweries all around the world?

Tom: Most of these collaborations on that list are Kjetil’s. So Kjetil, before starting the brewery, he visited many breweries in the US, he made a lot of friends telling them “I’m going to start a new brewery in Norway, what should I do?”. So he already had a lot of friends when he started, and later he came back and collaborated with them. Also by visiting beer festivals all around the world, he met all the brewers and he met together after that. Now we have made a few collaborations, especially last year—this year has been very busy with the moving and a lot of process going out internally, so we didn’t have much time to go out and brew. But Stephen Andrews, our barrel cellar manager has been out twice, brewing with breweries in Netherlands and Italy, and we are going to make a lot of collaboration brews this year.

Any collaboration brewery that you can announce so far?

Tom: We have a list with Swedish, Danish, English and Dutch breweries, and Stephen is probably going to the US as well.

About the alcohol culture in Norway. With so many regulations going on here about alcohol, how does it affect the day to day in the brewery? And what about the lack of raw materials here in Norway?

Tom: It’s very difficult to either sell and to promote our beers here in Norway. We have a small beer geek community in Norway that we are mostly using for our special beers. So we send them some previews, or some sneak peeks or hard to find, and they start the ball rolling, talking about the beers, and posting on social media. And we can do some marketing on our Facebook page, twitter or instagram. We can now show pictures of beer [it was just allowed one year ago in Norway]. But we cannot brag about the beers, and say “this beer is a wonderful beer”. We can just say “this beer”. We have to be very subtle. Appart from that, we are putting so much on marketing ourselves in beer festivals, and tastings in bars— when we launch a new beer in the market, we taste it in a special place, with beer people and a good dinner. We can also do some advertising in the B2B newspapers like this one that goes to every grocery in Norway.

Right now we are advertising Dark Horizon 5 special packaging. First version of Dark Horizon was the one that put us on the map abroad, with very nice reviews, the first one has 100 score in Ratebeer. It is an imperial stout with 15-16% abv, and there were not so many beers like that in 2006, so we made another 4 versions of it after that. We are launching it at Utobeer in London—a beer store—, and at Kihoskh in Copenhagen and in several bars in Norway.

You are one of the few European producers of Sake. Does its production stand totally independent from the beer, or does it influence how you make beer—or the other way round?

Tom: We started brewing sake at the same time we started brewing beer. Kjetil was travelling to Japan and discover sake, and all of its varieties in tastes and aroma. And he also heard that sake is one of the most difficult alcohol drink to make. The inherent process are so intricate. It is not like beer, where you put the yeast and that’s it. With sake, you have to be nourishing it all the time, and make sure it is always the same temperature. So when our sake brewer brews sake, he has to be at the brewery for two weeks in a row, almost 24 hours. He has to make sure that the temperature is right and the yeast starts in all the rice grains. And then on it is the same process than in beers, except that in sake you start with the fermentation, and then you mix in more rice and more water, and then it ferments longer than beers. The fermentation process takes 2-3 months, instead 2-3 weeks with beer. It is a long process, and out of that it comes a lot of flavours. It is in many ways very similar to making beer, but also very different, more delicate. It doesn’t scream out like beer does. Also, sake is very good to go with food.

Which kind of food?

Tom: Seafood is quite good, but also is meat. People thinks that sake just pairs well with fish and sushi, but in Japan they drink sake with everything. I think we have to teach people on that, but it is a long road until people starts appreciating it. There is not so much culture in sake here, and the taste is so different to everything we have food-wise in Europe.

You have shown us a lot of barrel-aging beers down in the factory. What are your future plans with barrel-aging, and in general for next year?

“We are really eager to start brewing and to start with new recipes, and get up where we want to be with being creative, being shown in the market as a brewery you have to look up to.”

Tom: We have a strong focus on project development. Next year, we are going to make each month a new different beer below 4,7% [this is the legal limit for beers to be sold in a supermarket in Norway]. And we are doing probably the same with higher alcohol beers, as well as collaborations and barrel aging. This year we had almost three months without brewing. In the summer we brew a lot of our regular beers, in order to have stock. Then we moved our brewery, and set it up again. So we are really eager to start brewing and to start with new recipes, and get up where we want to be with being creative, being shown in the market as a brewery you have to look up to. Also, we are going to make cider.

Apple cider?

Tom: Yes, it is a project we have been working on for almost a year—it takes a long time, because we are using the traditional way. We are going to make craft cider, not just sugar cider. It is going to be 100% apples, and naturally fermented. Actually cider—or at least fruit wine—had been brewed in Grimstad before. There was a company called Fuhr, making rubarb wine and apple wine. So it is a local tradition, and we have a lot of apples in Grimstad as well. We are looking for expanding with new products. We also have a license to make hard liquors, like whiskey or rum, so we may have some of this products as well.